MAIN TAKEAWAYS

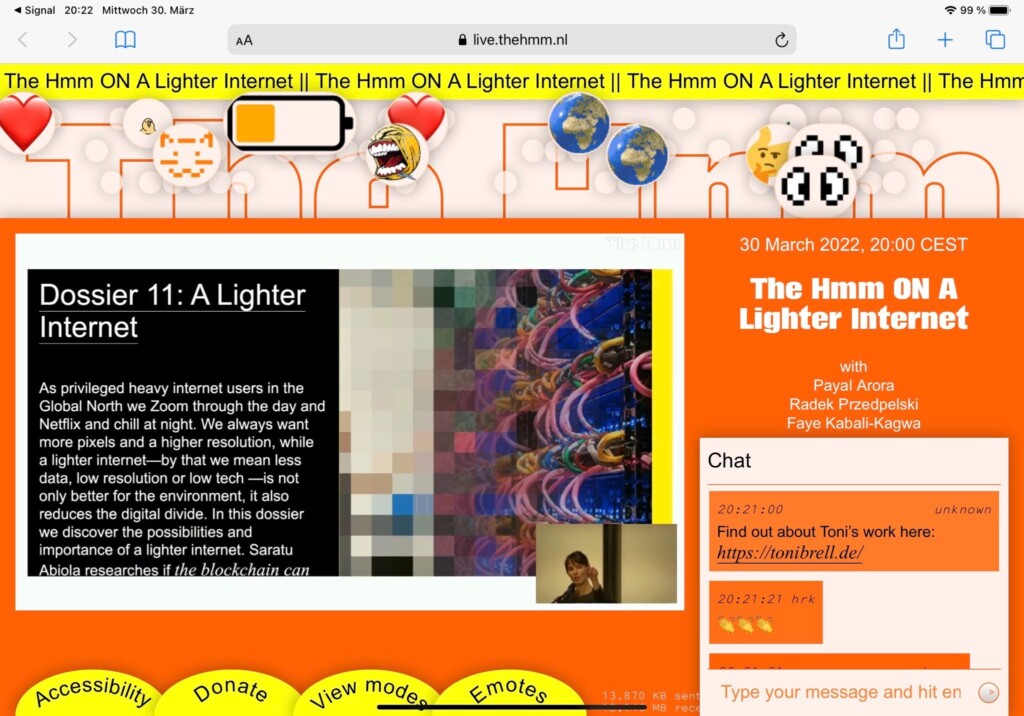

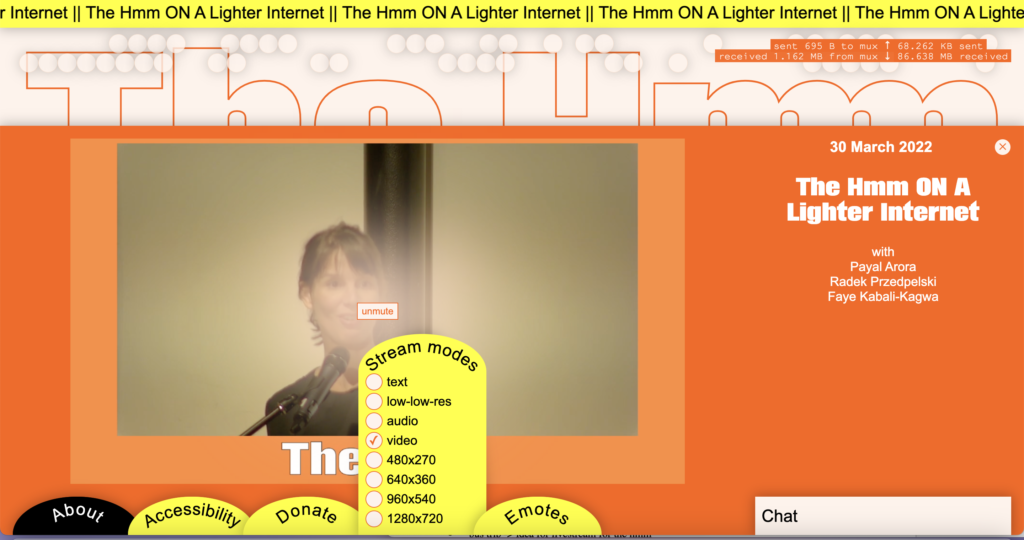

- Importance of low-barrier technology for accessibility

- Low-barrier technology and privacy trade-offs

- Oversimplification and managing expectations

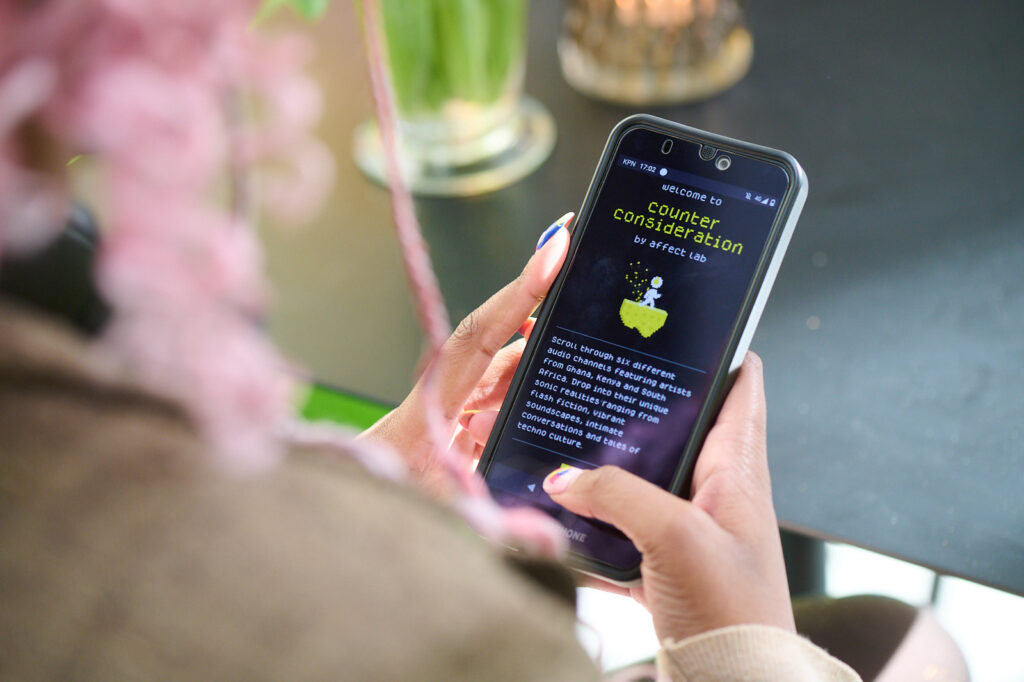

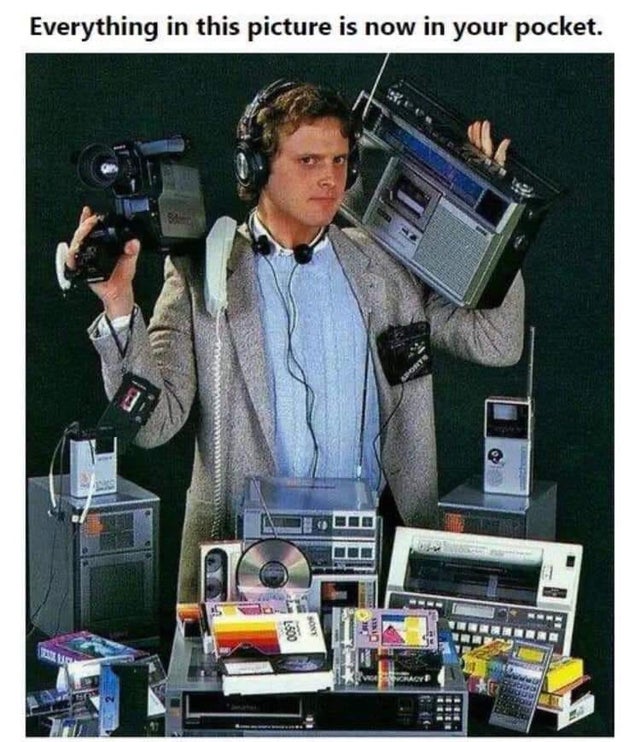

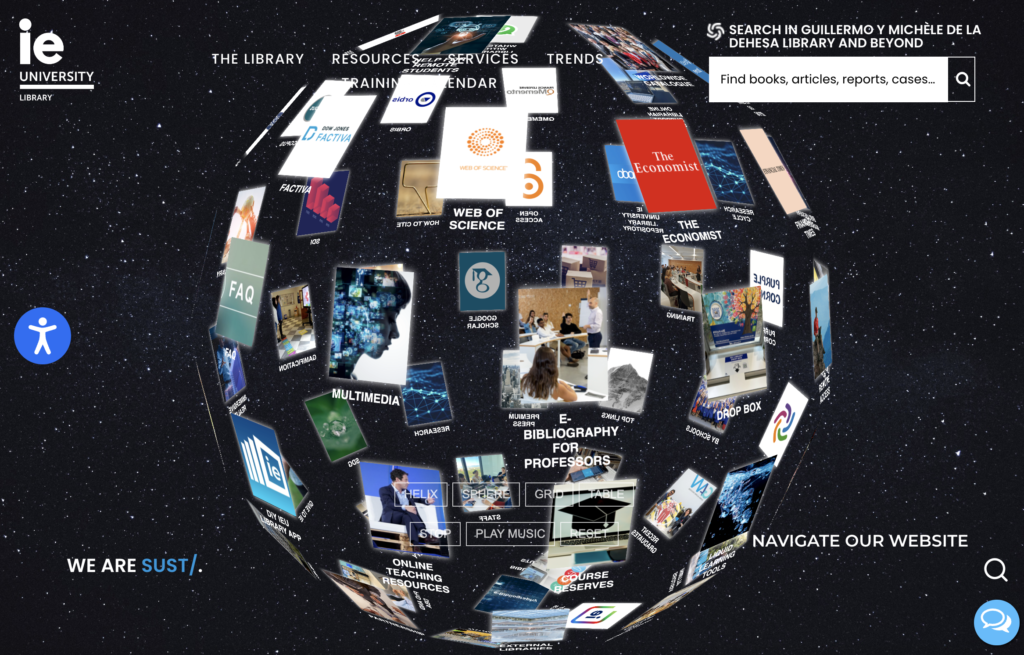

When designing our hybrid experiments, one of the fundamental considerations was how to make the experiments accessible to a wide audience. In this context, the accessibility refers to a technological ‘low-barrier’.

Low-barrier technology is important for ensuring that technological solutions to the question of hybridity are accessible to a broader and diverse population. It often exhibits the following characteristics:

- Accessibility: It is readily available and affordable, ensuring that cost is not a significant obstacle for users

- Ease of use: The technology is designed with a user-friendly interface and intuitive features, so that individuals with varying levels of technical expertise can easily understand and operate it.

- Minimal setup and configuration: Users do not need to invest a significant amount of time or effort in setting up or configuring the technology.

- Compatibility: Low-barrier technology is often compatible with a wide range of existing devices, software, and platforms, reducing compatibility issues.

- Inclusivity: It is designed to accommodate people with diverse abilities, languages, and cultural backgrounds, ensuring that it can be used by a broad user base.

- Support and resources: Users have access to adequate support, documentation, and resources to assist them in using the technology effectively.

- Low technical requirements: The technology does not demand high-performance hardware or advanced technical skills from users.

The privacy trade-off

When a low-barrier is facilitated through the use of existing – and familiar – devices software and platforms, privacy can be sacrificed. Big tech platforms that are less privacy friendly can be easier for a broader audience to use, because they are already familiar with them. In a scenario like this, it is a matter of choice: do you prioritise a low technological barrier, or privacy. Making technology more accessible might involve simplifying privacy settings or collecting more user data for customization. This can raise concerns about how user data is handled, stored, and potentially shared with third parties without clear user consent.

Equally, security vulnerabilities might not be purposeful, but instead they are the result of simplified and user-friendly interfaces. These might also inadvertently make systems more vulnerable to security breaches if not implemented with robust security measures.

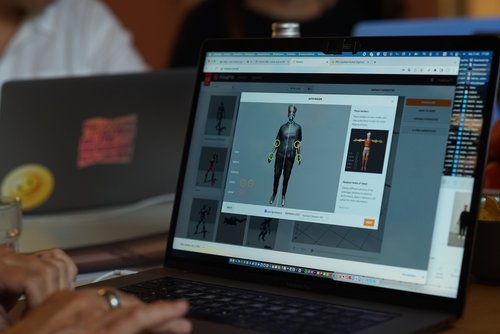

Build-your-own-avatar

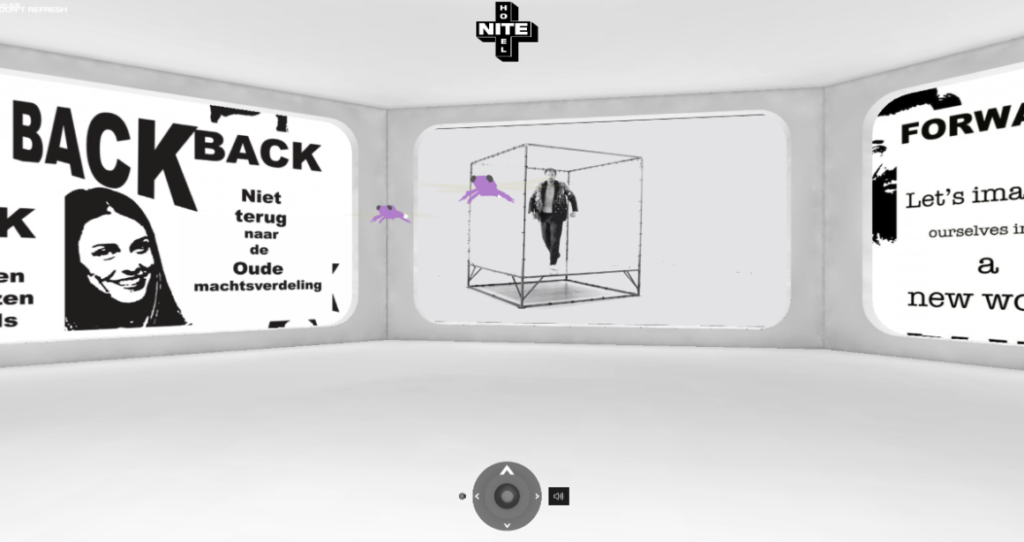

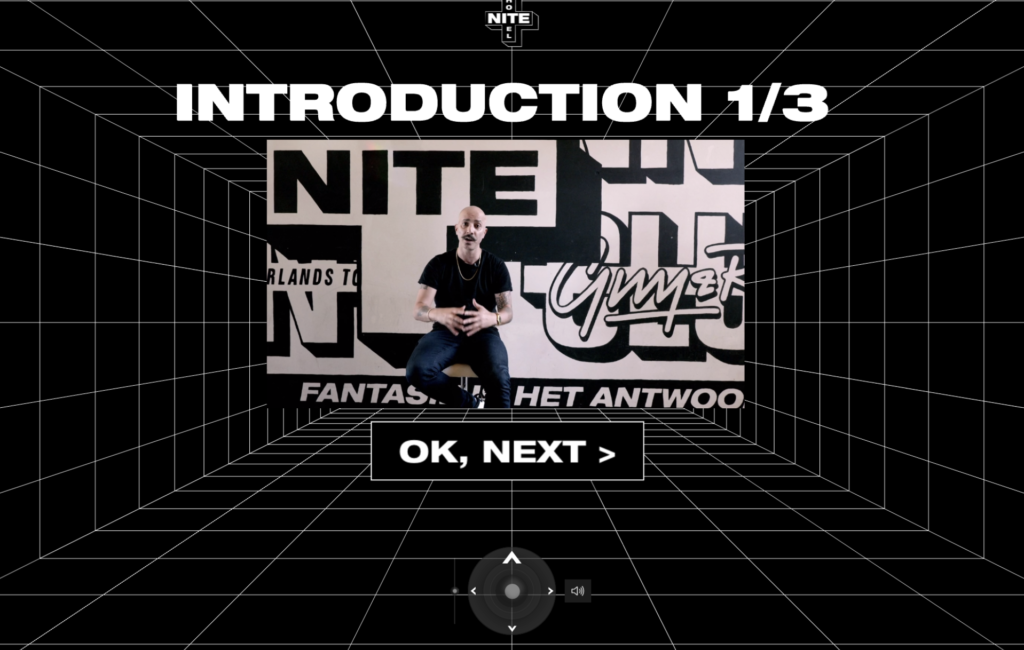

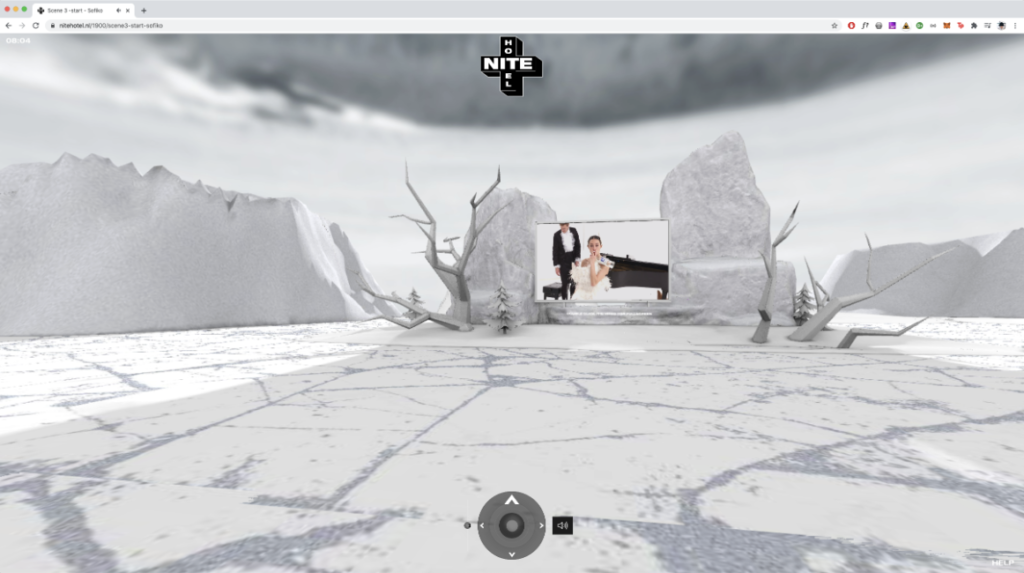

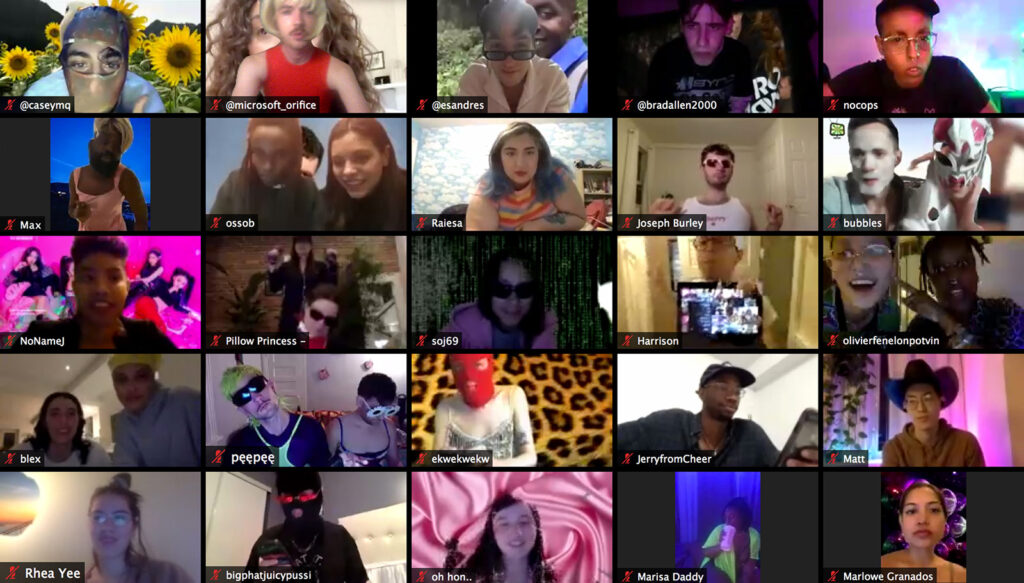

One of the aims of our Metaverses Cha-Cha-Cha experiment was to help people to understand that they could actively participate in the metaverse, and show them that the barrier to doing so was lower than they might have originally thought.

In the weeks leading up to the event, our guests are invited to create their own avatar at one of our in-person or online avatar workshops, or via this 4-step guide to building your own avatar.

“It is super easy to make your own 3D model, based on just a photo”

Workshop participant

The workshops allowed people to learn how to create their own avatar in Mixamo, using just a photo of themselves. They showed that it was relatively easy to build your own character – you just needed a phone and access to a computer. All of the software that we used in the workshop was available for free online.

“you can use your phone to make a picture that is good enough to make an avatar! […] you can do all this with non-proprietary software! And that it is quite easy to do, even if you don’t have any programming skills”

Workshop participant

Managing expectations

Simplified technologies and interfaces might limit users’ control and customisation options, which can be frustrating for advanced users who prefer more flexibility. This concern was raised during our build-your-own-avatar workshop. For workshop participants who were already familiar with 3D modelling technology, the workshop felt easy and perhaps a little basic. However, for others, it was the first time they had created a digital model and it was an exciting opportunity to engage with what previously felt like a complex activity.

A few of the workshop attendees felt that the workshop was not advanced enough for them, or that it did not teach them what they were expecting to learn. Particularly, they referred to the disappointment that they didn’t learn how to create an avatar (in unity) that didn’t look like them. One suggested that clearer information on the content of the workshops was needed when they were advertised.

“it wasn’t very new to me and I expected a bit more of it. Like actually building an avatar that doesn’t look like me, with weird features etc. Something that you can get creative with. But It’d be nice for people who want to get used [to] these technologies.”

Workshop participant