MAIN TAKEAWAYS

- The growing increase in internet use and the generation of more and more data impacts both the environment and the global digital divide.

- It’s important to create platforms that allow viewers with unstable or unaffordable internet access to join online events.

- Sometimes there can be a tension between accessibility and using open source tools.

- When thinking about accessibility, our decisions, choices, explorations, and interests are all situated in our individual contexts.

How can we make hybrid events more sustainable and accessible?

Over the last few years, there has been increasing awareness about how the internet contributes significantly to the world’s global carbon emissions. In 2020, every internet user generated an average of 1.7 megabytes of data per second. Online advertising accounts for 25% of the total internet bandwidth today. And all that data has to be stored somewhere, like in data centres that use around 1% of electricity worldwide and whose water-guzzling cooling facilities are predicted to cause drinking water shortages in the Netherlands.

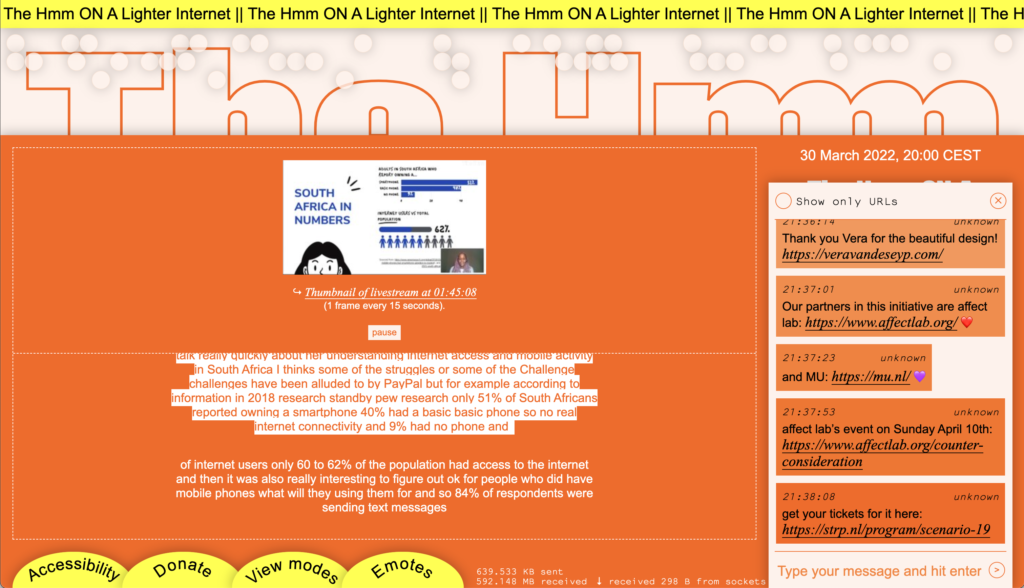

The growing increase in internet use and the generation of more and more data not only impacts the environment – it also exacerbates the global digital divide. While the internet has been a solution, and a lifeline, to the many problems caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it has also made more visible the billions of people worldwide (around 45% of the population according to UNESCO) who lack internet access, and the even larger number of people who lack access to affordable and fast internet. Those on the wrong side of the digital divide are disconnected from opportunities for education, employment, and social interactions.

There seems to be a growing tension between increasing connectivity to the internet and the impact of this on the environment. How do we balance these two things with one another? Especially when faster internet, more digital storage, and more connectivity are considered ways to increase development and access to opportunities globally. During The Hmm ON a Lighter Internet, which took place physically at Framer Framed in Amsterdam and online, we explored how the current internet experience is influenced by bandwidth access, and what a lighter internet actually means.

For the event, we brought together digital anthropologist Payal Arora, artist and media philosophy scholar Radek Przedpełski, and arts coordinator, cultural curator, and arts writer Faye Kabali-Kagwa. All the speakers joined remotely either due to COVID restrictions or due to their location, and our audience joined online and onsite.

Creating a ‘lighter’ platform

Since the pandemic started, we’ve been experimenting with a series of hybrid events that build on our knowledge of hybridity and the tools and platforms we can use to bring audiences together. The pandemic has shown us that we really have too little knowledge about how we gather and come together in online spaces. We believe that zoom fatigue is unnecessary and that digitisation can offer a lot to the cultural sector – as long as programs are hybrid and designed fundamentally differently from physical programmes. With (almost) every event we organise, we aim to explore a new format or tool—allowing our subject matter to shape the tools we create.

For The Hmm ON a Lighter Internet we updated our livestream platform, in collaboration with Karl Moubarak, with different view-modes—video (with a range of resolution options), low-low res, audio-only, and text only—to make it more accessible and to explore what low-tech and low-data internet solutions can look like. As an extra treat, we offered specially discounted (online) group tickets to stimulate people to watch our livestream together rather than watching on one computer or phone alone. By providing these different view modes, we also allow viewers with unstable or unaffordable internet access to join one of our events. Having these options also gave viewers a choice in how much data they were sending and receiving during the course of the event.

“I really enjoyed the content of the talks whilst watching within this experimental site. I think having the video embedded in the interface with the chat, emojis and even the orange border around it, really made it feel like i was more attending an event than just a ‘zoom lecture’. I loved that I could PAUSE it whilst it was happening! This was fantastic but didn’t take away from it being live!”

– Survey response from one of the audience members.

A multiplicity of view modes

With this experiment we wanted to explore the inequalities present in hybridity and who can even access the often data-heavy digital interactions and online events that those of us with affordable and stable internet access take for granted. In addition to these questions about access was the larger question about the ecological impact of heavy streaming. In our updated livestream platform, we added network traffic visibility, which gave each visitor information about how much data they were sending and receiving throughout the course of the livestream. We hoped that this information would provide visitors with the extra insight that is often hidden, sharing in the responsibility of our internet use.

For our audience that joined online, visitors responded that they did end up switching between view modes throughout the programme:

“Today I tested the different modes to see how they were, but ended my shuffle on auto. I felt like this was how I got the most info and since I was only focusing on the event I preferred it that way.”

– Survey response from one of the audience members.

Some viewers also said they liked the other modes, such as audio-only, as it allowed them to take a break from screen time but still follow the event. Another visitor noted that because their internet was cutting out a lot, the ‘text-only mode’ was delayed. However, in ‘video mode’ a poor internet connection would have caused the live stream to cut out entirely. Thanks to ‘text-only mode’, the visitor did not miss anything.

The thresholds of access

Implementing our ‘text-only’ functionality also allowed us to implement live-captions in our updated livestream platform. However, having the live-captions brought up a tension between accessibility and using open source tools. We used two live-captioning libraries, Google and MUX—one for the video and the other for real-time captioning. The live-captioning was auto generated, so it was not always clearly picking up the language, which is different when someone is editing the captions in real-time. In addition, by using the Google captioning library, we ran into issues with the censorship of language—swear words like ‘fuck’ were blocked out. From this process we learn that no matter what live captioning libraries we use, they have their own subjectivists and contexts, which can be colonial and ableist. This is a tension that many small organisations struggle with when trying to create an accessible platform within limited means.

Another choice we faced was whether to use MUX for video hosting and live-streaming. Early on, when building the first iteration of this platform, we had to decide how to host the videos and livestream. What kind of server would we use? We chose MUX – a private US company and the biggest video platform. We first explored the idea of self-hosting our livestream or trying distributed hosting across individual servers. While self-hosting is great, it is also very resource intensive, not the most ecological option, and requires a lot of maintenance. Due to its scale, MUX is efficient, and efficiency is also an ecological question.

When thinking about accessibility, it is important to highlight that our decisions, choices, explorations, and interests are all situated in the context of The Hmm as a cultural organisation running experiments and trying new things—we do not propose a solution or blueprint for accessibility and ecology that we want to scale across different networks, organizations and crises. Of course we offer our code under a public license, but the answers to these questions will differ in every situation. We are developing these tools from a specific urgency and within a specific context, and when you’re working on your own event or project you should do the same.

Credits

- The Hmm On a Lighter Internet was created by The Hmm. The speakers presenting their work were Payal Arora, Radek Przedpełski, and Faye Kabali-Kagwa.

- Design of the livestream website by Toni Brell, development by Karl Moubarak.

- The event took place onsite at Framer Framed.